A futurist’s guide to designing a better future

Futurist

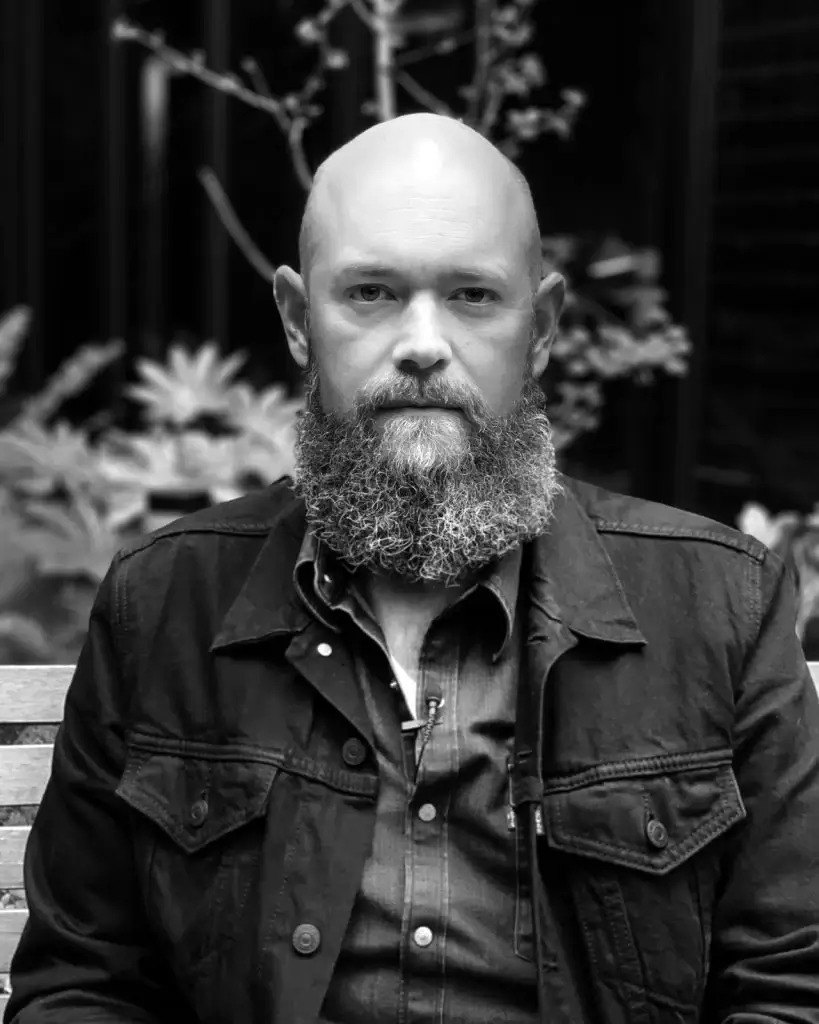

AHA talks with futurist Brian David Johnson on how much control we have over the future and how to see it as a story we can write.

As spring approaches, we’re hearing a familiar refrain: the return to normal. With so much attention on getting back to where we were before the pandemic, our minds are turning to the future. How should we be thinking about what comes next? More importantly, what are some practical tools we can use to plan and build a better future? One that moves us toward responsible innovation, shared prosperity, and more equitable and inclusive communities. To boil these questions down to actionable strategies, we talked with Brian David Johnson, professor at Arizona State University’s School for the Future of Innovation in Society.

The former chief futurist at Intel, Brian has written numerous books on crafting a better future, including The Future You, Science Fiction Prototyping and Screen Future. His consulting work spans governments, militaries, trade organizations and startups, and his writing has appeared in publications as varied as The Wall Street Journal and Successful Farming. When we spoke with Brian in February, the techno-futurist was sporting an understated flannel and a formidable pandemic beard. His background was a wall of paperback books. Our conversation ranged from the what the events of 2020 did to our sense of the future to the metaphysics of having a company vision.

Tell us what a futurist does.

Brian: Futurists are hired to help people and organizations plan for the future, whether it’s next quarter or next decade. It’s not so much a job as it is a way of thinking. Most of the people who come and study with me want the tools and techniques to be able to think like a futurist and then apply it to what they do. I’m an applied futurist, which means I help people articulate and create the future they want. My work is less about predicting the future as much as it is about trying to build a better one. I’m also a technological futurist, but you have people who are health care futurists, people who do work in defense and people who do work with cities. So there’s a lot of ways of taking this way of thinking and these tools and techniques and then applying them to whatever your passion is.

What do business folks tend to get wrong when they think about the future?

Brian: We all tend to think of the future as if it’s a fixed, inalterable thing that we have little control over.

In a way that lets us off the hook, doesn’t it?

Brian: The truth is that the future is the summation of all our individual choices. So in a real way, we make the future. We have a lot more control than we think we do. But that also means we have more responsibility.

And the one thing you can control when everything is uncertain is your own narrative.

The future seemed more malleable when the focus was on the latest technology trends at CES. Now it feels like our future is being shaped by forces beyond our control. Do we really have much agency in the face of forces like climate change, which seem to be defining our future?

Brian: As we think about the future in the face of these existential threats, it’s even more important to understand where we do have agency, where we do have control, and then start taking action inside of that parameter. We do not want to cede control at the beginning by saying it’s completely fixed.

At AHA, many of our clients are in this liminal place now, where even the middle-term view is muddled. There’s a sense that much has changed, but it’s not clear how that will play out. What are some steps leaders can use to find clarity when the future seems so foggy?

Brian: Again, start with what you can control. And the one thing you can control when everything is uncertain is your own narrative. You know that the future may be unclear, but it’s not fixed. And so start with foundational questions: What do we want the future to be? What do we want it to look like?

I tell people all the time that the way you change the future is by changing the story that you tell yourself about the future that you will live in. That is so incredibly powerful. Because if you can change the story that you tell yourself, if you can change the story that others are telling themselves, then they will make different decisions. They will make different purchasing decisions, different business decisions, different capital allocations. It actually allows you to begin to shape the future rather than trying to respond to it.

It’s interesting that the companies that are leading in ESG are the ones that have approached it not as a framework they have to respond to but as a new story of their company.

Brian: I think what happened in 2020 was a wake-up call for companies that they need to start grabbing hold of their own story of the future they want, because just responding to events doesn’t seem to work that well.

Having a clearly articulated vision for the future is everything in times of uncertainty. It has mass, it has density.

What happens when the larger narrative is fractured? Even the basic assumptions of the culture are in question now. Does this loss of shared context frustrate this process of articulating a vision for the future? Or does it make it even more important?

Brian: I think it makes it even more important. When there is no clear cultural narrative, we really need the coherence of an organizational narrative. Having a clearly articulated vision for the future is everything in times of uncertainty. It has mass, it has density. You’re saying, “This is what we believe. This is where we think we’re going.” You’re not saying, “This is what the future is.” You’re saying as an organization, ”This is the future we want. And this is the future we’re actively going to work towards and make happen.” That density, that mass, actually has gravity. It actually will bring people to you who share that vision for the future.

Do organizations struggle with this process of defining a “future we want”? It seems it requires a unique tolerance for heresy, a questioning of the basic pillars that hold up the current reality.

Brian: CFOs are the poor souls who feel this conflict the most. They’ll pull me aside in a work session and say, “What you’re asking me to do is make decisions that will make me less successful, that go against what I’ve been taught to do. But I agree with you that we need to make these changes to get ready for the future, because I want to be around in 10 years. I don’t want to be around just quarter by quarter.” And I always look at them and say, “Yeah, I know, it hurts, right? That queasy feeling you have, that pain? That’s the work of doing futures work. The cognitive dissonance is uncomfortable because you’re trying to overcome the inertia of the past, and you’re overcoming the inertia of where you are in the present.” We tend to hide from that tension by keeping the future abstract. That’s why I say you have to run right at it. When it hurts, it means the future is close. It means you’re doing the right stuff. Because if it’s easy, then you’re not doing the work.